- 04/03/2023

- 7 Min Read

- By: Christian Schaefer

Hidden Legends: Unveiling The World Of Unofficial Porsche Models

It’s hard to grasp just how small a company Porsche used to be. Today Porsche advertises itself best through owners, who share images of their cars painted in bespoke and specially chosen colors with personally selected interior trims and bits, but it wasn’t always like that. In its first few decades, the company did everything it could to produce the perfect sports car and beat the best in motorsport, and that often meant margins were razor thin. But keeping the company solvent meant more than just working around monetary constraints, as internal company politics, high model demand, and trim level changes forced quick decisions. Executives and engineers pulled out all the stops to ensure Porsche survived, leading to these curious and well-hidden oddities sneaking under the public’s radar.

1978-1980 Porsche 911 SC-L (Leistungsgesteigert)

Following the success of the 1973 Carrera 2.7RS, Porsche shifted their model development into a different gear. Emissions and fuel restrictions increased steadily as the oil crisis and the environmental impact of carbon emissions became too much to ignore. At the same time, Porsche executives were looking for an answer to the 911. Within several minds, the 911 had reached its apex as a sports car. The 930 represented the pinnacle of its design and remained Porsche’s fastest model through the seventies, but a new era was emerging from Stuttgart.

Photo courtesy of Bring a Trailer.

The air-cooled engines of the 911, 912, and 914 used tech principles from the early sixties, and the increasing emissions restrictions were making it difficult to get more power out of their engines while staying legal. On top of that, the 924 and 928 were in full swing by 1978 and were positioned by some on the company board to replace the air-cooled models once and for all. The decision split the board room, so the 911 stayed in production with an asterisk; if sales volume dropped below 25%, then the model would be axed. As we know now, that never happened, and it’s because a few Porsche engineers pulled out all the stops to prevent it.

1978 was the first year of the 928 and the 911 SC. The SC marked the first year the 911 was equipped with a 3.0-liter engine in its base trim, although the 180-hp engine was a letdown in power. A 15-horsepower bump over the outgoing 2.7-liter engine sounded fine, but the 911 also put on some weight with its return to an aluminum engine and transmission case. Making matters worse was the reduction in model variance. Porsche discontinued the 200-horsepower Carrera 3.0 available in ’77 to introduce the SC, leaving the 930 as the only high-performance 911.

Photo courtesy of Bring a Trailer.

The power figures looked even worse when compared to the brand-new 928. Its 4.5-liter water-cooled V8 was capable of 240 hp in European trim and gave the heavier grand touring coupe better performance figures than the SC. That wasn’t very comforting for enthusiasts and executives who viewed the 911 as the true Porsche. Making matters even worse for the 911 was Porsche Chairman Ernst Fuhrmann’s decree that engineers were to cease any work that improved the 911 post-1978. Several executives within Porsche were determined to keep the car around at any cost and created the company’s first “Powerkit” to do so.

Like today’s Porsches, customers in the late seventies could call up the Porsche factory and receive completely bespoke trims, colors, and options with a large-enough checkbook. The Department of Special Request handled those extras in what would later be called the Sonder Wunsch or “Special Wishes” program. Head engineer Rolf Sprenger, the man responsible for the first slant-nose 930, Bosch MFI in Porsche road cars, and the 964 Turbo S Leichtbau, led the department. His goal? Produce an engine that would meet the Carrera 2.7RS’s 210 hp without major directors, board members, or the public knowing.

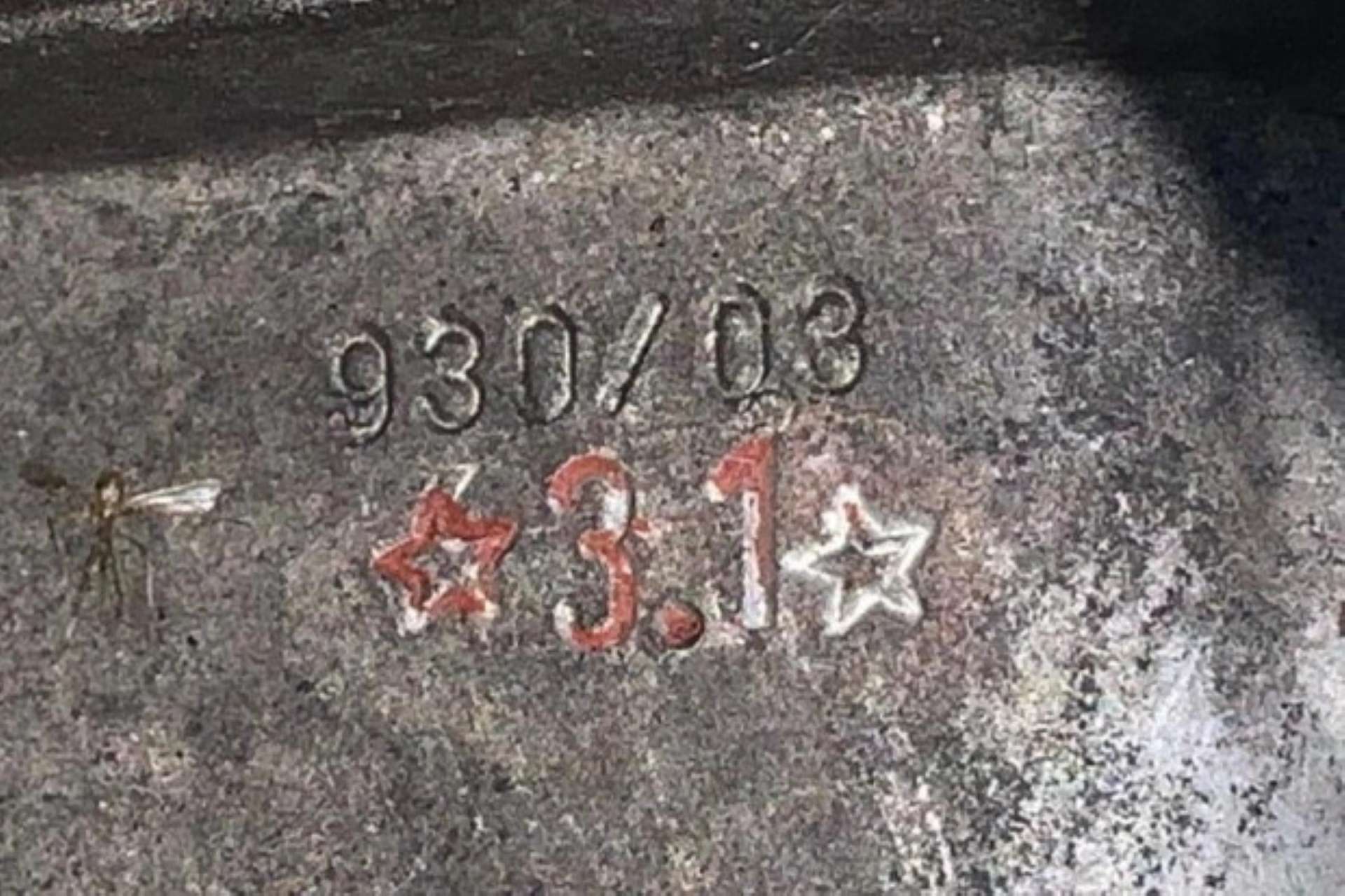

Development of the secret engine began in ’78, with the SC’s 930/03 3.0-liter engine serving as the basis. Sprenger and his engineers stripped the engine and replaced the 95mm pistons and cylinders with 97mm units. The cylinders were identical to the 930, and specially designed Mahle pistons delivered a 9.5:1 compression ratio—nearly an entire point higher than a standard SC. Then they went to Bosch and had a specially developed fuel distributor made for the new engine and its improved performance. Total capacity came in at 3122cc, while the official power output reached 210 hp and 206 lb-ft of torque.

Photo courtesy of Bring a Trailer.

Porsche also installed a larger oil cooler behind the passenger’s side headlight and put in a taller 5th gear to handle the extra performance the $3750 secret option provided. The latter wasn’t necessarily for a strength benefit but likely to give the 911 SC a higher top speed than the newly introduced 928. The special upgrade came with a name, too: Leistungsgesteigert, or “Increased Power” in English. Quite a mouthful for buyers and anyone referring to it, so the SC-L name was adopted.

The new engine met requirements and cleared German TÜV certification without anyone noticing. Piech and Sprenger had their engine, but they needed to sell it without word getting out. Ernst Bret, the Sales and Customer service representative at Porsche in that era, was notified of the upgrade and quietly mentioned the engine’s availability to dealerships by word of mouth to avoid Fuhrmann and others hearing about it. Those dealers were then only allowed to offer the package to customers who were disappointed enough by the lack of power to forego 911 ownership. As such, Porsche never officially offered the 3.1-liter as an option, only as a backroom deal to those looking for more punch.

Modern power kits carried designations like X51, X50, and X88, but the SC-L received no such code. A small brochure insert detailing performance figures, and a letter from Bret and Sprenger detailing the upgrades were all owners received to signify their unique, unofficial engines. Looking under the hood gave even less away as the 3.1-liter looked identical to the 3.0 when fully dressed. The SC-L’s only identifying mark was a “3.1” stamped on the engine case below the engine designation (not the case number). By the end of 1980, Porsche ceased the SC-L offering as they pulled 206 hp from the standard 3.0-liter in Europe. The American SC soldiered on with its 180 hp until 1984 when the 3.2 Carrera was released.

Photo courtesy of Bring a Trailer.

Official SC-L records are some of the scarcest due to their unofficial status. Cataloged production records don’t exist, so the true number of examples will likely never be known; however, those close to the project estimate 200-300 models made it out. All SC-Ls were sold in Europe as Sprenger and Bret didn’t share the project with American dealers, but a few have made it stateside in the years since.

As we now know, the 911 never left, and it was the 928 that met its eventual end in 1995. The 911 SC-L wasn’t the first quietly produced model, and it wasn’t the last, but it is perhaps the most secretive. Internally and externally, the 911 SC-L 3.1 was a whispered myth that few knew about.

1967 Porsche 911 deLuxe R.S. Ex. 13/66

The sixties were full of experimentation at Porsche, and the evidence is all over their products. Race cars were coming out yearly as the company was bent on dominating all forms of European motorsport, while the trusted 356 evolved into 911 and eventually the 912. Just a couple of years after their debut, Targa models arrived alongside larger engines and more options. The little company out of Stuttgart had a lot on its hands, and it needed all the money it could get.

In 1966, things were looking up as the 911 was a hit among buyers and the press alike. During the first two full years of production, ’65 and ’66, there was a single trim level, the 911. Options were limited in those days, especially in the performance department, so many cars had similar trim. Wooden trim, trunk-mounted Webasto gas heaters, and leather seats were all regularly equipped in the early cars, making them quite the luxurious package in the day. Unfortunately for Porsche, that hurt their margin.

The 911 debuted with a base cost of around 30% higher than the 356 it replaced, primarily due to manufacturing and developmental costs. People were happy to pay, but prices and equipment stayed stagnant for a few years, leaving buyers nothing to look forward to and Porsche with slowing sales. To remedy the issue, Porsche introduced the 911S alongside the base 911 in 1967. The new model was faster, lighter, and more agile than the base 911, providing buyers with a new fixation. However, what it really allowed Porsche to offer a much lighter equipped 911 as a more cost-effective entry-point. In theory, that would expand the 911 to more interested parties, thus driving more sales, and to their credit, it worked. But the move also put dealer inventory in a precarious position.

Leftover ’66 models were similarly optioned to the new S model but lacked its performance benefits. While that sounds alright, the cost of the ’66 cars was close enough to the S that execs feared buyers would skip the older car and go right for the latest and quickest model instead. Knowing that would hurt the company financially; they created a third trim level just for the last few cars—err, at least, that’s the currently accepted explanation.

At this point, Porsche hasn’t fully confirmed the existence or reasoning behind the short-lived 911 deLuxe model. The rediscovery of these cars came a little more than a decade ago, and subsequent research still needs to be answered. Finding information on them is challenging, but a dedicated group of enthusiasts has taken charge of the early911sregistry.org forum.

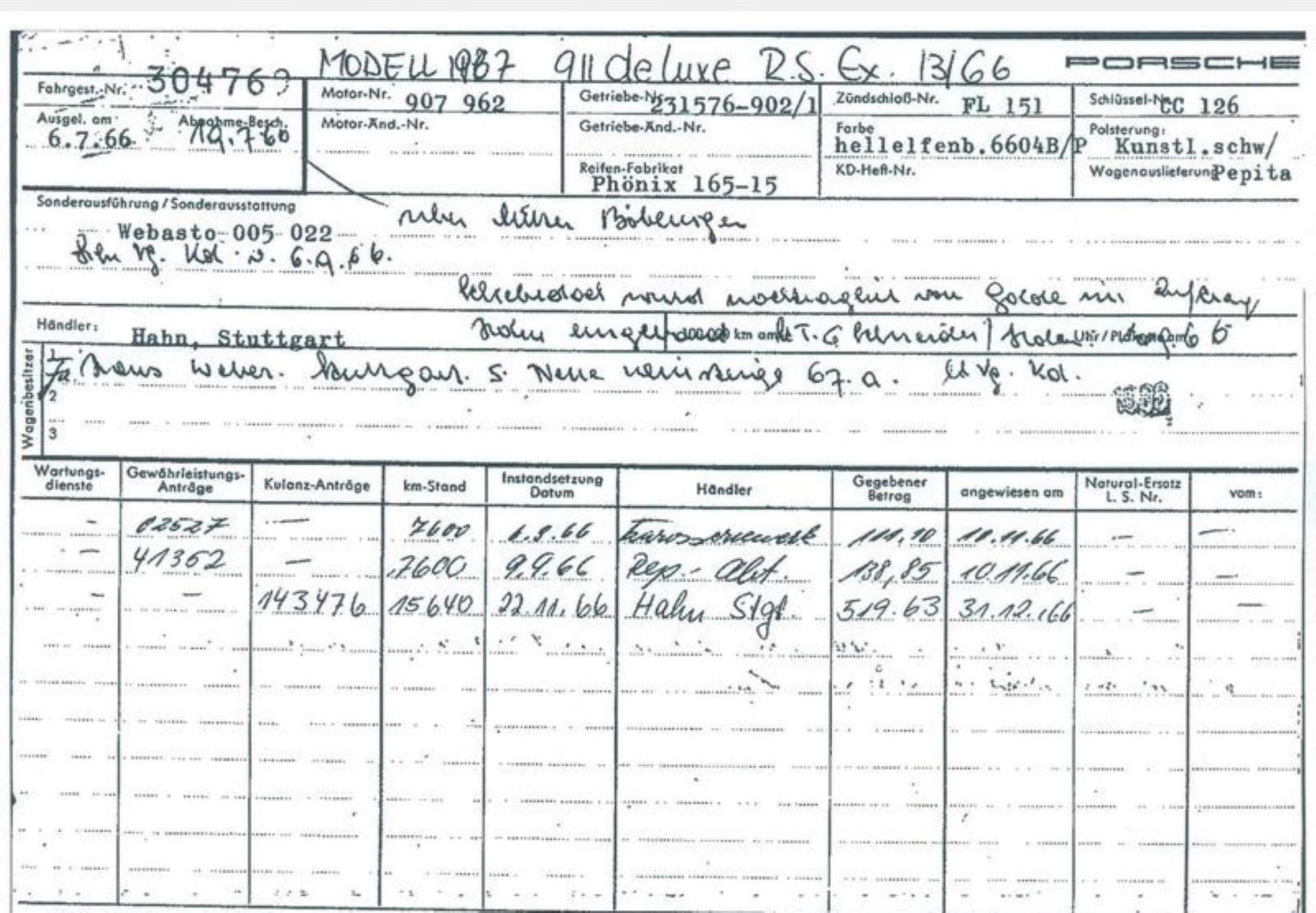

What is confirmed is that every 911 with the chassis code between 304703 and 304955 was originally a 1966 model built in the last few months of that model year. They were the final 253 examples made for the ’66 model year. Each example sported a wood steering wheel, wood dashboard trim, Webasto gas heater, tinted glass, an antenna, a loudspeaker, two exterior mirrors, and under-bumper fog lights. Allegedly, Porsche had already completed them in ’66 form before deciding to reclassify them as 1967 models, with some saying that more than a few were already sitting in European showrooms. They were called the deLuxe in official sales brochures, but behind the scenes on the factory build sheets (the Kardex), they received a much longer name: Modell 1967 911 deLuxe R.S. Ex. 13/66.

Porsche’s offered its short-lived gap-filler globally, with known examples sold in Europe and the states. But any mention of them disappeared from all literature and nearly Porsche history after they left dealerships. Uncovering the models took intense correspondence with the factory and digging through factory archives to confirm their existence. Yet, even with all of what’s currently known about them, there are still some question marks.

Chiefly among which is the explanation of the “R.S. Ex. 13/66” written on every Kardex. The initial and still only viable answer is that it refers to an internal bulletin at Porsche detailing the plan for the 253 examples. The German term for bulletin is Rundschreiben (hence R.S.). Their classification within Porsche consisted of the last two digits of the year preceded by which bulletin it was during that year, i.e., “13/66.” The certainly plausible explanation does have some potential holes, though.

Members of the "early911sregistry" forum have noted that the “R.S. Ex. 13/66” on each Kardex doesn’t align with how a native German would write it out. Then there’s the matter of the two “13/66” bulletins already found, neither of which refer to any model changes regarding the 253 examples. They are the F and M bulletins for Fahrgestell and Motor, respectively. The rundschreiben in question will likely be one regarding the sales department and will outline how and why Porsche made the changes. However, until that’s uncovered, we’ll be stuck waiting with the information we have.

1973 Porsche 914 "First 1000"

While the 911 has played the starring role in Porsche’s sportscar lineup, less expensive options have always supported it. Initially, it was the 912, and today it’s the Boxster/Cayman, but between those are a few of Porsche’s most unique vehicles. Debuting in 1970 was the VW-Porsche 914, a joint venture between the two companies.

Porsche and Volkswagen had been linked for several years, stemming from a verbal agreement decades prior from which Porsche was to provide its engineering services to VW for a certain number of projects. In this case, both parties needed a new model. The Karmann Ghia, VW’s sporty coupe and cabriolet, was getting up in age by the mid-sixties, and Porsche’s 912 was very similar to the 911 minus the flat-six, which left little difference in the lineup. The newly proposed joint venture would provide a versatile sports coupe that was as affordable as it was sporty.

Photo courtesy of Bring a Trailer.

Everything Porsche designed in the late sixties was meant to go racing; therefore, its new sports car was engineered around a mid-engine layout from its initial concept drawings. F.A. Porsche’s design grabbed traits from the 550 Spyder and 718 RS61 Coupe race cars and refined them into a more modern, squared-off shape featuring a removable fiberglass roof panel and pop-up headlights. Porsche engineers exclusively handled the development, so while it wore a VW badge in some countries and used many VW parts, it rode, handled, and stopped like a Porsche.

Winner of Motor Trend’s Import Car of The Year in 1970, the 914 was a massive hit for Porsche, selling over 100,000 units in the US alone between 1970 and 1976. Through that time, the 914 went over a dizzying amount of revisions. Early models had a non-adjustable passenger seat and a “tail-shift” gearbox with either a 1.7-liter four-cylinder or a 2.0-liter six. By 1973, a 2.0-liter four replaced the 911 engine, the passenger’s seat was adjustable, the headlight shrouds were black, the transmission became a “side-shift,” and the front bumper grew two skinny bumperettes. Other small things changed, but nothing was ever that different—except for roughly the first 1000 models delivered to California in 1973.

We know little about why these cars were built the way they were, but owners have compiled a list of defining features after examining their unique models. As the story goes, the demand for a 914 in the US was much higher than predicted, so high that there weren’t enough models slated to reach California, Porsche’s largest market. To remedy the 914 shortage, Porsche reclassified the first 1000 models readied for European delivery and refitted them with US equipment.

Photo courtesy of 914World member Tom_T.

The difference between US and European equipment wasn’t much. An MPH-reading speedometer, a fuel-injected engine instead of a carbureted one, some different badging, and different light lenses were the extent of the differences, except in this case. Appearing as an option on the 914 were vinyl-covered “sail panels,” the sides, and the top of the roll hoop/Targa bar. It was a popular option and the only place Porsche officially put the vinyl. However, those first 1000 models received vinyl-covered windshield frames—no model before or after was treated to that vinyl application as standard or as an option.

Then there were the mechanicals. The ’72 to ’73 changeover ushered in a series of mechanical and electrical updates to better the model, but because these were some of the earliest 1973 cars produced, they used several pre-’73 parts. Specific to the first 1000 were the pre-’73 non-hub-centric hubs, turn signal switch and harness, headlight switch and wiring, rain tray, and doors. The latter meant that they were the lightest 1973 examples, thanks to their lack of safety crash bars. Beyond the vinyl around the windshield frame, dealerships fitted them with “Dan Gurney” wheels made by Western, though many have replaced them with one of the numerous other 914 wheels.

All models were reportedly sold in California during the early seventies, though there aren’t any records of how many remain today. Those that do remain carry a uniqueness, like a 2.7RS or 968 Clubsport, but without all of the fanfare. In reality, they’re just a standard 914 with some weird and mismatched bits, more akin to misprinted artwork than a special edition. Does that make them any more valuable? Probably not, but they’re a fascinating look back at what Porsche had to do fifty years ago to meet demand in America.